Baricitinib

JAK of All Trades

The Story of Baricitinib, the JAK Inhibitor Curing HIV and Treating COVID-19

Baricitinib’s journey started on November 4th, 2010: “I remember that day. I’ll remember it for the rest of my life,” said Christina Gavegnano, PhD. “[An] idea came when a guest lecturer was speaking about a class of drugs called JAK inhibitors.”

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are drugs that block excess inflammation.

“In that moment, everything I ever knew about HIV, everything I ever knew about inflammation, came together all in a split second ... faster than that,” she said.

A Student’s Epiphany

Christina Gavegnano, PhD

Gavegnano is an associate professor at the Emory School of Medicine and has a dual appointment in Emory College’s Center for the Study of Human Health. She also directs the Gavegnano Drug Discovery Program, a translational research lab studying disease pathogenesis and inflammation, emphasizing drug discovery and immunomodulation with small molecule inhibitors, including JAK inhibitors, the hero of the baricitinib story.

Gavegnano recalled her revelation in that guest lecture: a hunch that JAK inhibitors, known anti-inflammatories, would play a role in the eradication of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) — a disease affecting about 1.2 million people in the U.S. and more than 40 million worldwide.

“Within two hours of binding and entering a cell, HIV activates its JAK/STAT pathway,” she said. “And in my head, I immediately knew that JAK inhibitors can block that. They can block the bad, downstream inflammation that drives the disease, which prevents people from being cured.”

That evening, Gavegnano sent an email to her boss with the subject line “HIV eradication idea,” and she dedicated her research to the study of JAK inhibitors baricitinib and ruxolitinib.

Hard Work and Human Trials

At the end of her PhD thesis, Gavegnano’s research had generated enough data to head to Phase II human trials for HIV treatment, which were successful.

“We showed that we're able to decrease, even for a short duration of time, key inflammatory markers that drive disease progression in people living with HIV,” said Gavegnano.

Later, after running a 60-person study at Emory in collaboration with Emory Professor of Medicine and Global Health Vince Marconi, MD, Gavegnano and her team were ready to take it to the next level: pitching their data to Eli Lilly. The pharmaceutical giant acknowledged the strength of the team’s data, but despite initial interest, months passed without further action.

Then, February 2020 came. As the world and Eli Lilly were looking for answers to the COVID pandemic, the JAK inhibitor research for HIV was not high on the pharmaceutical company’s list of priorities.

“I felt my heart drop, because I knew what this drug could do,” said Gavegnano, but her disappointment would not last long.

JAK of All Trades

As a scientist who works closely with Emory’s Office of Technology Transfer (OTT), Gavegnano says she’s always thinking about different applications for a drug.

So, when she found out that baricitinib had been shelved as an HIV treatment, she said, "Wait a minute, the mechanism is the same for all viral infections.” Both the HIV and COVID viruses thrive by inflaming the human body, and if the JAK inhibitors had shown promise with HIV, then it stood to reason that they should also work with treating COVID.

In collaboration with Marconi, the team went to the National Institutes of Health, which granted them an unprecedented, direct path to a Phase III study. The expedited timeline was made possible because baricitinib, the JAK inhibitor tested, was already on the market as an FDA-approved treatment for rheumatoid arthritis; the team was now repurposing the drug as a COVID-19 therapeutic.

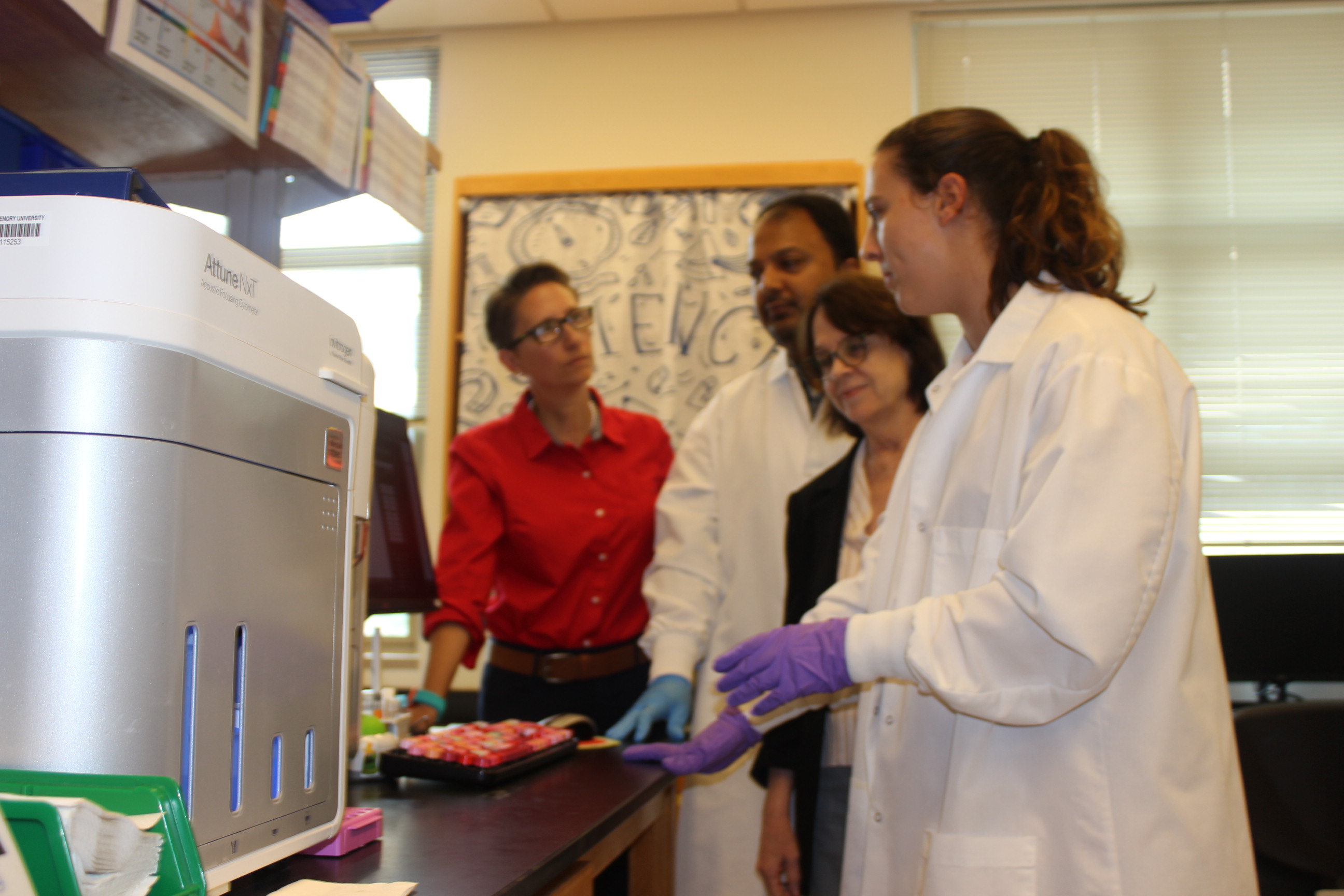

Gavegnano and her team use a flow cytometer to measure cell characteristics in their HIV cure research.

On November 19, 2020, the FDA granted emergency use authorization (EUA) to baricitinib for the treatment of COVID-19 in adults. It was the fastest speed on record from drug idea to EUA in history.

“I remember seeing [the EUA approval] pop up on my Google news feed. That’s how I found out, and I immediately called up OTT,” said Gavegnano. Laura Fritts, then OTT's Chief Intellectual Property Officer, hadn’t yet seen the news, because she had just finished negotiating the license agreement for baricitinib with Eli Lilly nine minutes prior. Gavegnano recalls Fritts’ words: “Congratulations. You’re actively saving lives.”

The drug was later granted full FDA approval as a treatment for acute COVID-19 in May 2022. Now, more than three million people globally have taken baricitinib for the viral disease.

“I thought we were going to cross the finish line for HIV first,” said Gavegnano about baricitinib’s approval. “The world has a weird way of working, but I'm not sorry about it.”

A Potential Cure for HIV

Even with the COVID response ongoing, people hadn't forgotten about the HIV research that came from Gavegnano’s PhD thesis.

As she and her team were preparing to present data at the 2023 International AIDS Society in Brisbane, Australia, Gavegnano got a stunning call from another team presenting at the conference.

“We have a case report of an individual who may be cured of HIV with your drug,” they said.

The team behind the call? Alexandra Calmy, MD, PhD, and Asier Sáez-Cirión, PhD, professors at the University of Geneva Hospital and the Pasteur Institute. In Australia, they presented 19-month, long-term remission data for the Geneva patient, a person with HIV who was treated with baricitinib. As of 2025, the Geneva patient is on the official HIV cure list and is the first and only HIV patient to take a small molecule drug without receiving a mutated stem cell transplant.

Next Steps

Gavegnano is now co-leading a clinical trial using baricitinib for HIV cure research, along with Marconi and Andrew H. Miller, Professor and Vice Chair for Research in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences in the School of Medicine. The study will examine whether extending JAK inhibitor therapy beyond six months can further deplete HIV reservoirs and lead to long-term remission, in the absence of traditional antiretrovirals.

Gavegnano lab members pose for a photo. L to R: Kate Siegel; Christina Gavegnano, PhD; Sourav Sen Gupta, PhD

“Our models predict that HIV reservoir decline will take 2.9 years to eradicate from someone's body. And if we can do that, it's game over,” said Gavegnano. “It's something that has already changed the world, but it's something that will change the world even more.”

In addition to researching JAK inhibitors’ effects on COVID and HIV, the Gavegnano group is beginning studies looking at the interaction between bariticinib and depression, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and more inflammation-driven diseases.

“We now have intellectual property across many diseases, and now we have seven ongoing human trials of baricitinib,” said Gavengnano.

“Commercialization is a word that's not often paired with academia,” she continued, “and what I've learned is that it can and should be for the beautiful reason that it helps us continue to make discoveries that save people's lives.”

— Jenna Woods

Read more about Emory’s research impact on HIV and COVID-19: